Latest

Lessons from Auschwitz: Lower 6 Students Humanising History

Iona (L6) - on-stage speaker at the school assembly

This year, two of our Lower 6 students, Iona and Caroline, both currently studying History at SQA Higher Level, participated in the Lessons from Auschwitz programme. As part of our commemorations of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz and Holocaust Memorial Day, Iona delivered a whole school assembly and Caroline has written the opinion piece below to share her knowledge with the St George’s community.

Lessons from Auschwitz offers students across the UK the opportunity to develop their historical understanding of the Holocaust and apply that learning to contemporary issues. After completing online seminars and a one-day visit to Poland, participants enhance their skills and show leadership in education about the Holocaust - demonstrating their commitment outside the classroom through sharing the legacy of this dark period in history.

Humanising the Holocaust

written by Caroline (L6)

On Monday 27th January 2025, the world marked 80 years since the liberation of the most notorious site of the Holocaust – Auschwitz, in Southern Poland. The Holocaust constituted a genocide under the regime of Nazi Germany and defines the very worst of human malice and the erasure of much of the Jewish population of Europe. It can be defined as, ‘The murder of approximately six million Jewish men, women and children by Nazi Germany and its collaborators during the Second World War’.

In early November last year, I had the privilege of a visit to Oświęcim – a small town near Krakow better known by its German name of Auschwitz – with the Holocaust Educational Trust as I undertook the Lessons from Auschwitz project. The Trust brings together students from all over the country to bear witness to the Holocaust and spread education of its key warnings and implications for the present and future. Before our visit to Auschwitz, we met for a seminar to discuss the historical and contemporary relevance of the Holocaust. Of the many important messages which we explored and took away, the one about the individuality of each victim was critically obvious to me. It is all too easy to speak of the 6 million Jewish people who died without comprehending the loss of individual lives, hopes and experiences. Objectively, the Holocaust was a genocide and it is important not to deviate from the stark reality of the atrocity at its core. However, on their own, incomprehensible numbers like 6 million and infamous sites such as Auschwitz do not convey the human level of the Holocaust and ultimately serve to dehumanise those who were killed, furthering the agenda of the perpetrators who intended their erasure.

80 years on from the end of the Second World War and the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps, I would like to share the individual stories of just a few of those affected by the Holocaust - both survivors and victims - in the hope of humanising and appreciating the varied and colourful lives of the Jewish people affected by the Holocaust, from all ages, beliefs, countries, and walks of life. These individuals’ stories help us to understand the Holocaust on a human platform, acknowledging not a conglomerate of faceless victims but instead incredibly varied individuals, connected only by their Jewish religion, and the horror of their persecution under the Nazis and their enablers.

Ota and Katerina Margolius – Prague, Czechoslovakia

This photograph was taken of Ota and Katerina Margolius, a young couple, in Prague sometime around the end of 1930. Ota was from Prague, serving in the Czech army for 18 months in 1925 and going on to work for his father’s distillery and later put his passion into sports. He was a talented sportsman, going on to play for the Czech national hockey team and win prizes for ice skating and athletics, it was through his involvement in the world of sport that he met Katerina. Katerina was from Austria and had attended art school in Vienna, putting her skills to work as a milliner after graduation. A year after their wedding in October of 1930, they had a daughter, Ines, setting up the beginnings of a life in Prague.

Before the Holocaust, one in seven people in Prague were Jewish. By 1939 they were subject to antisemitic laws, two years later deportations to ghettos and camps had begun. In the years that followed the Jewish population of Prague were moved to concentration and death camps, and by the end of the war, the Nazis had murdered 65% of Prague’s Jewish population. Ota, Katerina, and Ines were sent to Terezín – a ghetto just north of Prague. The three were due to be sent to Auschwitz together some short while after, but Ota was kept behind to bury those who had died inside the ghetto and was then killed in Terezín shortly after. Katerina and her daughter made it to the camp, subsequently surviving the move to Bergen-Belsen and then Buchenwald concentration camps. Ultimately, Katerina and Ines were sent back to Terezín ghetto which was liberated in the early summer of 1945. The only survivors among their family, they moved to Chile after the end of the war. Ines would go on to have her own children, second generations survivors – the grandchildren of Ota and Katerina.

Berta Rosenhein – Leipzig, Germany

In 1929, Berta Rosenhein is photographed on the grass, aged six and ready for her first day of school. She has a school cone, a gift traditionally given to German children on their first day of school and filled to the brim with sweets, chocolates and stationery. Berta remembers this as a happy time, with her mother Irma who taught her music and entertained her with trips to the theatre, and her father Walter. Berta and her traditional school cone illustrate something very important about the Jewish population of Germany – that they considered themselves Germans first, and Jewish second, integrating well into society and accepted by their communities. With the slow but certain rise of antisemitism in 1930s Germany, many German Jews sought to flee to neighbouring countries. A huge diaspora immigrated to Europe, the UK, and North America. Luckily, Berta was taken on the Kindertransport, the organised rescue effort from Germany and its territories of Jewish children to the UK, at the end of 1938. She lived with the Sampson family in England for three years until 1942. Of her immediate family she was the only person to survive through the Holocaust. Her father Walter died of an illness before the transportation of German Jews to ghettos, concentration camps and death camps, and her mother Irma was among the first in Leipzig to be transported to Riga, where she was killed by the Nazis. Berta remained in England after the war, marrying and becoming Berta Hertz. She has donated a wealth of information, and material to the United States Holocaust Museum, endeavouring to educate about the life of the Jewish community before the Holocaust, and her family’s own story.

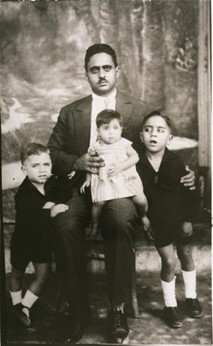

The Mordo Family – Corfu, Greece

The young girl pictured in the centre of this photograph is Perla Mordo. She sits on her father Jacob’s knee, surrounded by her elder brothers Shabtay and Moshe, her mother Ester is not pictured. The Mordo family was a close family, from Italian controlled Corfu, and Perla, the third of six children recalls an incredibly joyful childhood, remembering ‘peace and music, it was a beautiful life believe me’. Corfu had a relatively small Jewish population of 2000 who actively practiced Judaism and were mainly Orthodox, before the Holocaust the community was vibrant with four synagogues and established tradition. While Italy was under the fascist rule of Benito Mussolini, Italian officials regularly refused to deport Jews, offering them an unprecedented level of protection in a Nazi territory. However after the fall of Mussolini and his regime in 1943 the Jews of Corfu became exposed to deportation and persecution. The whole Mordo family was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Ester and the three youngest Mordo children – Regina, Rachel and, Elio – were immediately selected for the gas chambers, and were murdered. Jacob and the eldest boys were put to intensive work in the camp. Jacob was killed in Auschwitz while his sons were moved to other concentration camps including Stutthof, Moshe did not survive. Perla and her older brother Shabtay were the only survivors of the Mordo family, Shabtay emigrated to Israel, while Perla went to the US. Perla lived a long life, passing away in 2021. She had two daughters, and a number of grandchildren, who survive the Mordo family despite their persecution and murder by the Nazi regime.

The stories of these individuals prompt us to view the survivors of the Holocaust in a more personal light. It is crucial for us to view the Holocaust on a human level to fully appreciate the vibrancy of the Jewish community before it, and crucially to apply the lessons learnt from it to our own world through an understandable and relatable lens. With a worrying rise in Islamophobia, antisemitism, and a concerning shift towards extremism in the modern world, it has never been more important to recognise the contemporary relevance of the Holocaust, and education’s place in moving towards a more tolerant society. The lessons which the world should have learnt from the Holocaust are being shunned in contemporary issues such as the persecution of China’s Uyghur Muslim population, religious intolerance, persecution and murder which hauntingly echo the past. The humanity of the Holocaust is crucial in understanding why and how such events were allowed to occur, and perhaps more importantly in recognising and celebrating the identities and cultures of those who were silenced. Today, knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust is crucial, and the human level is perhaps the most significant when it comes to remembrance, learning, and prevention. I would like to leave the words of Martin Niemöller, as a reminder of the duty of all of us in standing up to hate and intolerance in our society, in the hope that we may learn a valuable lesson from history.

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Martin Niemöller, 1946